Review: Andreas Gursky

White Cube, Mason’s Yard

23 March - 5 May 2007

by Aaron Schuman

Originally published in Hotshoe International, April/May 2007

Over the last two decades, Andreas Gursky has built a colossal reputation, creating photographs that ‘do not so much mirror as embody [the] gorgeous, cold-hearted spectacle’ of contemporary reality. In their epic size, saturation and subject matter, these images envelope and then overwhelm viewers, often lifting them above the apparent chaos of life to reveal the self-imposed order of the manmade environment. Generally, Gursky is most insightful when he transforms the ordinary – a hotel, a beach, a supermarket, an apartment block - into the extraordinary. But recently, Gursky has turned to the extraordinary itself as his main source of inspiration. In doing so, he has managed to maintain the impression of the sublime within his work, but in a sense, has also alienated the viewer from the scenes depicted, presenting the eccentric or the exclusive rather than the everyday.

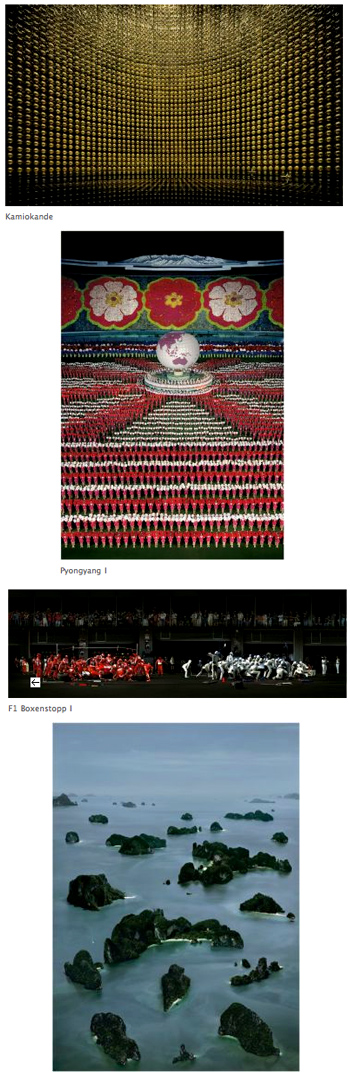

Gursky’s new show at White Cube is a striking, bizarre and incredibly revealing affair, pinpointing exactly how far photography has come within the elite world of contemporary art, as well as how far it is willing to go to meet the expectations of this voracious marketplace. Apart from Beelitz - an eerily beautiful, aerial view of an asparagus farm tended by low-wage workers – the focus of the exhibition remains firmly in the spectacular. Kamiokande depicts a celestial golden chamber, buried deep within a Japanese mine, which has been designed to detect of the smallest known particles in the universe. More explicitly, Gursky’s Pyongyang series derives from photographs taken at the the Arirang Festival, a celebration held annually in North Korea honoring of the late Communist leader, Kim Il Sung. Like the event itself, the images are gaudy, awesome and absolutely terrifying, as eighty thousand people are rigidly choreographed to form a shifting human mosaic of patterns and images. Of course, it is no secret that totalitarian regimes particularly favor this type of pageantry as a means of both executing and flaunting their supremacy over the masses. And the medium of photography certainly lends itself to such events, particularly from a high vantage-point, as in Rodchenko’s celebrated images of Soviet demonstrations, or Riefenstahl’s camera-work in ‘Triumph of the Will’. The problem that arises within the context of Gursky’s oeuvre is that much of his previous work acutely exploits this cunning visual strategy in order to emphasize how ‘free-willed’ societies have similarly imposed a rigid system of structure and choreography upon themselves. This juxtaposition – of freedom and control, of chaos and order – is what has made many of Gursky’s images so incredibly provocative and powerful to date. Aesthetically, the Pyongang series retains this patented sense of distance and sublimity. But because the event itself is contrived to be just that, the pictures lose much of their force in that they simply evidence a blatant display of tyrannical control, rather than cleverly provide insight into the workings of humanity when it’s freely left to its own devices.

Continuing on the gallery’s lower-ground floor, the show descends from the sublime to the ridiculous. Gursky’s recent series, F1 Boxenstopp, consists of Formula One cars sitting in their respective pit stops, being frenetically tended to by their spaceman-like teams. Each pit was shot individually at various Grand Prix races around the world, but they are presented in pairs, with members of an indeterminate crowd peering down into the action from the hospitality suites above. The images have been so heavily manipulated that they are both and outlandishly slick and entirely unconvincing; awkward tableaux that recall both Rejlander’s Two Ways of Life, and the worst of contemporary cut-and-paste advertising. When considering the artist’s intentions for making such uber-glossy work, it’s difficult not to imagine that, in this series at least, Gursky is primarily catering to his jet-set clientele more than to his own artistic ambition.

That said, another of Gursky’s new series, James Bond Island I, II and III, is both mesmerizing and critically potent. Based on aerial photographs made of the Thai island, Khao Phing Kan (used as a location for Man with the Golden Gun), these topographic collages allow Gursky to create an imaginary archipelago that lures the viewer in with its white-sand beaches and azure seas, whilst also alluding to the megalomaniacal nature of both their fictional context and cultural magnetism. Elegantly balancing on the border of the believable and the artificial, they elegantly critique the pursuit of escapism through commonly held fantasies of seclusion and paradise.

Gursky’s photographs are well known for being the most expensive within the contemporary market – just last month his 99 Cent II Diptychon sold for a record-breaking $3.3 million dollars. Looking at this recent show, it is difficult not to conclude that Gursky’s own creative decisions may have become somewhat clouded by such commercial success and the all-access pass that has accompanied it; but it is interesting to note that it was a diptych of a banal ninety-nine cent shop, rather than a elite or luxurious scene, that commanded the highest price at auction. Perhaps it is worth considering that, despite photography’s vast ambiguities and extreme malleability – particularly within the digital age – it is imagery firmly grounded in a more common reality that truly remains most desired.

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2008. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.