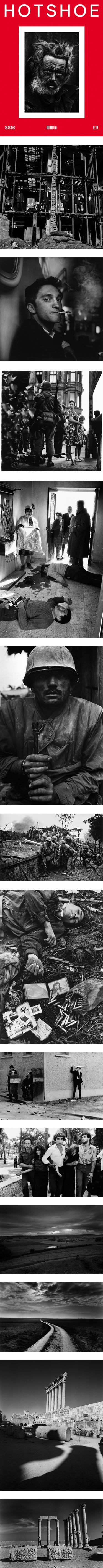

DON McCULLIN: The Extended Interview

This interview was originally published in Hotshoe Magazine, Spring/Summer 2016

Over the course of nearly sixty years, Don McCullin has established himself as one of most accomplished, respected and celebrated photographers of our time, producing some of the most iconic and important images of both the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. From the 1950s gangs of North London to the ruins of the Roman Empire, from the rise of the Berlin Wall to the Troubles in Northern Ireland, from the horrors of the Vietnam War to those of Biafra, Beirut, Iraq and elsewhere, as well as the beautiful bleakness of the Somerset countryside - where he now resides - and so much more, McCullin has maintained a consistent, compelling and often troubling vision that serves as an original and provocatively moving testament to both history and humanity today. This year, McCullin has been named as the Photo London Master of Photography 2016, with an extensive exhibition to open at Somerset House in May, and a special retrospective show curated by Tate’s Simon Baker and Shoair Mavlian to follow at Rencontres d’Arles 2016 in the summer. Earlier this spring, Aaron Schuman visited McCullin at his home in Somerset:

AS: Aaron Schuman

DM: Don McCullin

AS: To start, what first inspired you to want to be a photographer?

DM: I didn’t really want to be a photographer. Basically, I never really went to school. My father died when I was thirteen, which I felt very angry about; my whole life was destroyed when he died. We lived in two damp rooms in Finsbury Park – he had asthma, and died at the age of forty. The irony is that my work is framed for exhibitions in Finsbury Park – by a man a called Jonathan Jones – and his business is where there used to be huge coal-yard that I would steal coal from. I used to think, “I’m not going to sit here in this stinking damp room, watching my dad die” – this was when I was twelve or thirteen – so I’d go over there at night with a sack, and nick coal. I could’ve been put into borstal for that – there was a harsh prison system, even for juveniles. Luckily I wasn’t, but I definitely had an attitude problem as a child. So I officially left school when I was fifteen, got my first job working on a steam train, and then did my National Service in the Air Force. They sent me to a photographic unit, and wanted me to sit in RAF Benson in Oxfordshire, painting numbers on Second World War aerial photographs. But I said that I wanted to go abroad, so they sent me abroad. I went to Egypt, and then to Nairobi during the Mau Mau Uprising. While I was there, we printed all day long, bulk-processing aerial reconnaissance photographs of the jungle – hardly inspiring. But the guys told me that if I gave one of the pilots thirty quid, he’d fly to Aden on the milk run – as they did, day in and day out – and bring me back a new Rolleicord. So I did.

AS: Why did you want camera?

DM: Well, it was a beautiful camera, and it was thirty quid – brand spanking new in the box. I came from a background where we had nothing in my house. There wasn’t even a book in my house as a child. But when I returned to England, I pawned that camera for five pounds, as I had no interest in it. Then my mother paid the five quid, got it out of the pawnshop for me, and I started to hang out with this gang of boys, documenting them. I took that famous picture of the boys in their suits on a Sunday afternoon, and the next day they got involved in trouble with the police – a policeman got killed at the bottom of my street. That night I was with my wife in Muswell Hill, which was a slightly nicer place than Finsbury Park, so I wasn’t involved; I wasn’t there.

AS: Were you hanging out with the gang socially, or did you already regard yourself as a photographer who was simply documenting them?

DM: I went to school with them. They were villains and crooks. Some of them were murderers and bank robbers – all different kinds of people. But it was never in me to want to be a law breaker; I used to do terrible things like the others did, but I didn’t want to be incarcerated in prison with a load of thickos.

AS: But nevertheless you found them compelling?

DM: It was a social prison that was hard to get out of – you had to have a strong will to get away from them. They put pressure on you all the time, to hang out with them and do bad things like fighting and destroying things. One night, I got off of a bus near where I lived and a gang of them were all by the bus stop. Near this bus stop was a big gent’s outfitters shop, and they said that they were going to get some suits out of the shop window. They scored it with a diamond ring, and kicked it in. While they were saying, “What do you fancy, Don?” I looked, and there were two policemen down at the end of the road. Suddenly, I put it into top gear – I was gone. I could really run in those days, so I ran through the streets thinking, “I’m not going to be arrested for something I’m not involved in.”

So that was the way I grew up – with all this intimidation and stuff going on. And sometimes I used to enjoy it, of course. I hated the police – in a way, I still do to this day – I hated authority, and I hated incarceration. But after that famous picture of the gang was published in The Observer, I was offered every job in England – just because of that one picture.

Then I got married and went to France. I was in the Café de Flore in Paris, and I looked over this bloke’s shoulder who was reading the newspaper and saw that famous picture of an East-German soldier jumping over the barbed wire. I said to my wife, “After we go back to England, would you mind if I went to Berlin?” This was in 1961, and my wife would never say no – she was very kind and sweet. So when we got back to England, I rang The Observer and said, “I’m going to Berlin”, grabbed my last seventy quid out the bank, bought an airline ticket and rolled up in Berlin. I stayed there a week, and shot everything on the Rolleicord.

AS: What were you looking for in Berlin? Were you there to get a “story”, or were you trying capture something more?

DM: I imposed it upon myself to go – they were building the wall, and I thought I should just be there. Why was I saying this to myself? I wasn’t a photojournalist; I wasn’t anything. But there was some driving force in me that was directing me to these places. When I came back, I won some little press award, and The Observer gave me a contract for fifteen guineas to photograph two days a week: Friday and Saturday, because they were only a Sunday newspaper. Then a couple of years later, I went into the office one day and the picture editor said, “Would you consider going to cover the civil war in Cyprus?” By then I’d learnt a little more about photography, and I couldn’t believe what I was hearing – I said yes, of course I would. So I went to Cyprus and won the World Press Photo Award. Then after that, both a German magazine and a London magazine asked me to go to Vietnam, so I started to go to Vietnam in 1965.

AS: Was Cyprus the first time that you experienced combat?

DM: Real gun battles; it was the first. Strangely enough, it took place in a town called Limmasol, which was just a few miles from the RAF base where I was last in the Air Force, before I was sent home and demobbed. It was amazing; these coincidences have happened in my life all the time.

AS: Were your first encounters with combat in Cyprus terrifying?

DM: It wasn’t terrifying; it was exciting.

AS: Was that excitement what made you want to go back to conflict zones again and again?

DM: I’ll tell you right now, Robert Capa had been killed in 1954 in Indochina, and there was this job vacancy – I wanted to be, not Robert Capa, but the best war photographer in the world, which is a really silly thing to say. I knew that, but I thought that you should look for an area that you’re suitable for. I came from Finsbury Park, I was tough, I wasn’t afraid, I challenged everyone who challenged me, I challenged everything. I thought, “I’m cut out for this job.” When I came back from Cyprus I realized that – with my speed, and my attitude about war – that’s where I belonged. I suddenly found my little place in the world.

AS: Many of your photographs from Cyprus focus on the victims of war; particularly women and children, often crying over dead husbands and fathers.

DM: I also found that I was very suited to that. I’ve got a picture of a shepherd who was murdered – they used to kill each other, the shepherds. I went to this Turkish shepherd’s house one day, where they had laid out his body, and his son was about my age when my dad died. He was brushing flies off of the corpses head – off his father’s head. All of the people were looking in with the light behind them, and the shepherd’s wife was kneeling beside the body. I was cut out for that, because when my father died he was brought back to our house from Whittington Hospital. My father lay in his coffin in one of our two rooms for a couple of nights, until they took him away and buried him in Highgate.

AS: When you say that you were cut out for it, do you mean that you had the emotional strength to deal with such situations?

DM: I thought, “That boy is me, really.” I know it sounds silly, but before I went to Iraq recently, I sat in the airport in Turkey for seven hours, as if I’d been turned into stone; reading, waiting, dignified. Other people were having fistfights at the airline desk, screaming that they’ve missed their flights. I can transform myself.

AS: Is that a matter of control, or a certain emotional numbness?

DM: It’s numbing down the pain. I was with John Le Carre one day in Beirut. We went into this office to get his accreditation, which took about half and hour, and I was sitting there looking at Le Carre, and the clock, and the man sweating behind the desk. When we got out I said, “Sorry it took so long in there for you,” and he said, “On the contrary, I found it thoroughly interesting.” It’s funny the things I remember. I throw myself around in my own mind, saying to myself, “Did you really do that? Did you really see that?” It’s been such a long, compacted life.

AS: So after Cyprus you started to go to Vietnam on assignment?

DM: I went back and forth to Vietnam for several years. Most of my journeys were pretty futile, unless I was lucky enough to have my trip coincide with a huge event, like the Tet Offensive in 1968. Also, in 1972 I did very well; so well that I got expelled by the Vietnamese government. Anyway, during the Tet Offensive I was with the 5th Marines. In those days, because there was no “embedding”, I roamed around totally free with the rank of Major. Can you imagine? This was a man who came out of the Air Force with no rank at all.

AS: What was your incentive whilst you were photographing in Vietnam? Were you trying to expose something about the war, or trying to change the world, or were you simply there for the thrill of it?

DM: That’s a very good question. There are two ways of looking at it. The thrill of Vietnam cam from the fact that you had the biggest pyrotechnical show in the world going on right in front of you. And you had the most dramatic looking men fighting a war – you’re not going to miss out with American Marines when you’re up close, and I was as close as you could get. But when I was amongst dying children, I had to temper my attitude, and work in a terribly different direction. The war itself was Hollywood, but the other side of it was reality. Hollywood contaminates people’s minds; it’s full of crap, and nonsense, and stupidity. When you go to war, and you see men with half their faces missing, their brains and guts hanging out, bodies lying in pits with their eyeballs falling out…get real, Hollywood. I suppose they feel that by not showing too much blood and guts they can make money and not have a conscience.

AS: Did you feel that the publications that you were working for had a conscience, and would show the realities of war?

DM: Absolutely – particularly The Sunday Times; they really had balls. The two men who worked there – Michael Rand and David King – were brilliant. I was surrounded by talent in the ‘60s – the floodgates opened, and all the talent in England came rushing out. We hadn’t had any privilege or opportunities in our lives, but suddenly there was this extraordinary revolution. I travelled with extraordinary writers, who became my tutors, but I was dyslexic – I still am to this day – so I carried a slight inferiority complex on my shoulders. I had broad shoulders when I was a young bloke, and carried all kinds of angst on them.

AS:. Do you still carry this angst, or no more?

DM: I still have the shoulders, but they’re not as big as they used to be. I had shoulders that would carry a wounded American marine away from a battle, which I did one day. There’s a famous piece of film from the First World War, which shows a soldier coming through the trenches with a man on his shoulders, and he looks up with tired eyes. I’ve done that, because sometimes you’re so pissed off with people dying, and with taking pictures; taking advantage and taking liberties in a way. You think to yourself, “Do I have the right to take other people’s pictures when they’re dying?” I don’t. I’ve worked all the philosophy out on this; I know exactly what my role is, where I should be, how I should behave, how I should approach a situation, and how I should accept a certain amount of guilt. I’m my own walking psychiatrist, because I know that if I put a foot wrong, people are going to say terrible things about me. I don’t want that – I want people to admire what I do, and to understand that I’m the courier, the pigeon. I don’t want to be attacked by people.

AS: But in fact, you’re celebrated. You, amongst a number of other photographers – Larry Burroughs, Eddie Adams, and so on - are often credited with shifting the public’s opinion of the Vietnam War, particularly in America, and in some sense inspiring the anti-war movement.

DM: It didn’t work though, did it? Eddie Adams took that picture, and it took another five years for the war to end. We helped to change opinion, but we didn’t change it entirely.

AS: There’s a certain cliché about war photographers – that they go to war because they want to change the world...

DM: Is that what you think?

AS: No, but a cliché line that war photographers sometimes give to justify their actions is that their intentions are to expose and show the horrors of war, and then the world will be so shocked that it will change. I think that, quite often, it’s for much more selfish reasons, so I’m just curious…

DM: Really, what it is is this: “We’re going to go and have a really nice, exciting time. Let’s hope we can get away with it, and come back alive.” It doesn’t work for some of them – a lot of guys get killed. I went to Vietnam as a photographer, hoping to do the best I could, to show people my pictures, and to horrify them. I was going there for a purpose, and The Sunday Times didn’t mess about – they’d lay out pictures of dead North Vietnamese soldiers without a problem – so we had a mission. But at the end of the day, there was an adrenaline-junkie thing about war as well. It’s very exciting being shot at getting away with it, even when at the time it’s quite scary and you’re thinking that the top of my head will go any minute now. When I came under fire I was really worried, because I knew what the consequences would be. That so-called “adrenaline rush” isn’t a very good way of describing it.

AS: What’s a better way of describing it?

DM: It’s very difficult to describe. It’s playing Russian roulette really; there’s no other way of putting it. There was a day when one of my cameras got hit by a bullet. I didn’t have a helmet or flak jacket, and there was a sniper that was killing all these guys around me. I was running across this paddy-field with ten Cambodian soldiers; one young boy was carrying a flag – he must have thought it was still Napoleonic days – and he was the first to get hit. Then all of the other guys got hit and I hid behind the radio operator, because he had this big square metal thing on his back. That didn’t work, because bullets were lashing from all over, so I thought, “Fuck this, I’m not going to get killed”, and threw myself down in the water and slime. But to keep my cameras dry, I was dragging them along the side of the paddy-field. I didn’t see the bullet hit my camera, but when the water ran out, I ran like fuck across this field. I could hear bullets and mortars going over, and I was zigzagging in order to be a bad target. When I finally got back about three-hundred yards, away and out of range, I was covered in mud and thought that I’d better check my cameras. And wallop, there was a bullet-hole in my Nikon.

AS: It’s interesting, because as you tell that story I can see the thrill of it – as much as the terror – in your eyes.

DM: Thrilling, yes. But there was more terror than thrill in that moment, I can tell you.

AS: In such combat situations, what are you thinking about when you raise the camera to your eye and look through the viewfinder?

DM: First of all, composition – I want to get the composition right. I’ve got no time to be the great master of anything; I just have to get the picture. Also, I always worried about exposure – I didn’t want to take a picture that was underexposed and then be killed. There are so many things going on, and I’ve always put my hands into fate. But you’ve got to stand up, and you’ve got to get the composition right. I just gambled and gambled, all the time.

AS: In terms of composition, are you trying to get as much information into the frame, or is there something more formal going on in your mind?

DM: I’m definitely trying to get information across, but within a formal composition. And I’ve got to do that in a split second; I’m dealing with 125th of a second – it's the blink of an eyelid. Most people have a bit longer than that to make a decision, so I’ve got to be bloody quick. I try to foresee things, and always be two steps ahead. My mind has been sharpened like a pencil, like a needle. I’m like a surgeon in a way: I have the sharpest scalpel in the world, and it’s my brain. I’m always under pressure, always worried, and in those days you had to wait weeks to bring the film back to England and have it processed. Can you imagine the discipline? I had such discipline, and I’ve still got it. I had a great respect for film, and knew you mustn't spoil or abuse it. I always used to go to Vietnam with thirty rolls of Tri-X film – nothing more, nothing less.

AS: Whilst you were going back and forth to Vietnam, you were also shooting in Northern Ireland and elsewhere.

DM: Yes, I went to Derry in 1971, and got expelled from Vietnam in 1972. I was also in Bangladesh in 1971.

AS: Was Derry also on assignment for The Times?

DM: I wasn’t staff, but I was on contract and used to suggest stories to The Sunday Times. I was coming into London on the train – from Hertfordshire to Liverpool Street Station – and I’d see these homeless people sitting in doorways and shuffling about. So one day in 1969 – when there was a lapse; nothing international going on - I went into the office and said, “We should do something about homeless people”. They said, “Well piss off and do it”, so I spent six weeks photographing homeless people. I think it’s the best thing I ever photographed. I went every day, parked my car up about a mile away, wore really old clothes, and carried a Nikon F under my overcoat. Then I would gradually bring the camera out. They’d all start shouting and jumping, “What the fuck are you doing?!” I liked both the danger and the challenge of it; they were quite violent people, but no one ever tried it on with me.

AS: How would you compare photographing in Derry to photographing in Vietnam?

DM: In Derry, the risk was being hit in the head with half a brick, because I didn’t have any protection. It was dodgy, because thousands of bricks and bottles were flying through the air and they’re just as dangerous as a bullet. But at the end of the day it had a massively exciting touch to it, and I thought that I could slightly indulge myself because no one there was getting killed. But of course they were being killed. I spent six weekends photographing in Northern Ireland, but I missed the most extraordinary weekend – Bloody Sunday. I was so angry. It was an impossible situation really. Everything is, even today. When I see homeless people, or the immigrant situation, I’m ashamed of it; I’m ashamed of seeing these children sitting on the border of Turkey and Greece shivering. I’m ashamed of humanity.

AS: Do you think that shame is one of the central themes of your work?

DM: I don’t think that I’ve ever glamorized war, and you could glamorize it if you wanted to. In the end, I realized that the people who really pay the price of war are the civilians. But the big question I had to pose to myself was, “What the fuck has it got to do with photography?” I’d have conversations about this with myself while all of this was going on. Sometimes, when I’d see a dying child, crying and dragging itself across the road with it’s insides hanging out of it’s bottom, I’d say to myself, “What’s this got to do with photography? Why am I here?”

AS: And what’s the answer?

DM: Incredibly, the answer is shamefully confusing. It put me in a very bad place, because I felt that photography was meant to be something that we enjoy. Am I enjoying watching this child, whom I can’t help, die? I went to a camp in Biafra with eight hundred dying children, and as soon as they saw old Whitie coming in, they said, “Oh good, it’s a white man – he must be bringing aid.” But we weren’t; we just came in with Nikon cameras around our necks. Morally, I know how good and bad – how evil and how wrong – it was.

AS: Perhaps your photographs act as a standing testament to these events, not just in the short term, but in the long term?

DM: No, I think they’ll be forgotten, along with history. Already I don’t count for much. All I do is photograph the landscapes around here. People say “I love your landscapes”, but people shouldn’t love any war picture I’ve taken. When they say “love” they don’t mean it like that – they mean they were moved by it. But the landscape, as you see it now in all its glory, is also under threat. How many cows can you see in the fields today? None. When I first came here, these fields were covered in cows, even the fields at the end of my garden. The farmland hasn’t gone, but the farmers have. All they do now is cut the hedges around here; they get big EU subsidies. The EU shouldn’t be giving farmers money to cut hedges – they should be giving the, money to grow food, because the world’s population has exploded. When I came into photography – as the slightly thick, uneducated, insecure person that I was – I thought, “Photography’s going to be really great, because no one will ask me any serious questions. I’m just going to do portraits and pictures of things; it’s not political.” But my whole life has been political. All the work I’ve done is political, and now I’m looking at a political situation with this bloody landscape. Even the landscape is political.

AS: When did you begin to photograph the English landscape?

DM: I started seriously in 1992. I was still going off to wars and things like that, and when I came back here I was very lonely. I had all kinds of funny lifestyles – different kinds of women in my life, who were plaguing me. I had a beautiful American wife, who was amazing-looking but, to be honest, was actually a total bitch, and didn’t like coming here; it was a huge mistake. I’ve often had conflict with women, because in the end they can try to dominate you.

AS: Is independence something that you’ve needed, both for your career and otherwise?

DM: Well, independence doesn’t make for a good marriage, you see. But I’ve got great family who have all been very generous to me, because I’ve abandoned them all the time.

AS: Returning to the landscape, what inspired you to start photographing at home; what were you looking for in this landscape?

DM: I was looking for solitude, in a way.

AS: Because of your professional work, even your landscape photographs – which are quire dark and bleak at times – are often associated with the psychological impact of war.

DM: If you look out the window, there’s an emptiness here.

AS: Is emptiness calming and peaceful to you, or is it something slightly more sinister?

DM: I find it chilling. You look at these landscapes, with what I call “Wagnerian” skies – metallic skies, and the trees without leaves. It’s as if they’re naked, skeletal. There’s definitely something about it that mixes with the war memories, with charred and burnt earth, and I always see the landscape in black-and-white. People often say to me, “I love your landscapes, but they’re a bit war-y looking”. But it’s because they’re empty and skeletal; it looks like devastation more than beauty. I wouldn’t want to photograph this landscape with all the leaves out. I’m no Ansel Adams. I look for drama – drama is the key factor in all my work. When I look at the work of Alfred Stieglitz, I see so many tones. I’ve printed so many pictures, and worked in the darkroom for so long, I know my tones. The darkroom is an amazing, wonderful, and cunning place – it’s a place of mind-searching. By dodging and burning, I engage in the landscape work; there’s definitely some cunning goings-on in that darkroom.

AS: What goes through your mind in the darkroom?

DM: Perfection – you’re striving towards the perfect print. In the darkroom, you can almost hear the applause, the accolade of this perfect print. If I know that I’ll be printing the next day, I go to bed at night worrying, and sometimes I actually scan the negative in my imagination whilst I’m lying in bed. I know all of my negatives – I know where they succeed, and where there’s trouble. It’s just terrible the way that photography is blackmailing me all the time. I’ve been blackmailed for the last sixty years of my life by photography, and it’s been the greatest love affair; it’s fantastic really.

AS: Do you consider yourself an artist?

DM: I’ve got to be very careful about the art side of things; the art world is a huge problem for me. I am not an artist. Today, every photographer in America – if not the world – want’s to be called an “artist”, which is bullshit. Why do you need a title? All you need to do is to take good pictures, and offer them to people. When I have exhibitions in galleries, people say, “If you don’t like the art world, and you don’t like the title of artist, why are you exhibiting your work in an art gallery?” But I believe that you must liberate your work. I want photography to be in your face; I want it to have a voice, and I can’t keep all of these pictures in my print room forever. But I don’t want it to be worth a lot of money. I’ve just applied for visa to go to Syria, so that I can photograph the destruction of Palmyra. I did the most beautiful pictures of Palmyra several years ago for my book, Southern Frontiers. The other day, I saw a copy of that book on Amazon for a thousand pounds, which is absurd. It was only a fifty-pound book, but because ISIS blew up the temples in Palmyra, someone pushed up the price on Amazon. I don’t belong in that world.

AS: What originally drew you to the sites that you photographed in Southern Frontiers?

DM: I began thinking about a writer called Bruce Chatwin. He and I went to Algeria many years ago, to do a story about immigration for The Sunday Times, and we stayed in a small Roman town. Subsequently, thirty years later, I suddenly thought, “Christ, I’d love to go back to that Roman town.’ It was 1994 when I started Southern Frontiers, and I published it in 2010. I went to Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Baalbek, Palmyra, Tyre – where there’s a big Roman hippodrome – and so on.

AS: What compelled you to photograph Roman sites?

DM: You could spend ten or twenty lives studying it, and you’d still be scratching the surface of the Roman history. As I was photographing these Roman temples I thought, “These are amazing, it’s extraordinary being here, and it’s such a privilege. But can I not hear the cries of the pain and suffering of people – the slaves who perished to build this?” Because that’s how they were built: on cruelty, starvation, pain and brutality. So in a way, I was standing there, admiring something that I knew was built upon cruelty and shamefulness.

AS: So again you return to cruelty and shame, even in the most glorious of environments.

DM: We all do, you see. We condemn, but we still tread that road.

AS: Do you associate wealth with cruelty and corruption?

DM: Yes, I do. I’m very fortunate, but it was never about money with me; it was about getting my name under my pictures. And still – even now, when I’m over the age of eighty – I want to liberate my work and keep the voice shouting, even if it’s fading over the decades. But I have no interest in money; I’ve already been rewarded by having this life. I was a stupid, ignorant, semi-hooligan boy, with a chip on his shoulder, and I’ve been rewarded by getting out of Finsbury Park. I left all that, educated myself, travelled more than anyone you’ll ever know in this world, and have had a really amazing life; that’s been my reward.

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2016. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.