'Review: "Taryn Simon - A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters" @ Tate Modern

by Aaron Schuman

Spring 2012

This interview was originally published in Aperture, #205, Winter 2011

The notion that the pursuit to encapsulate and convey objective “truth” via documentation—in particular through text, image, or a combination of the two—is inevitably contrived and doomed to failure is by no means a new one. In 1936 James Agee and Walker Evans received an assignment from Fortune magazine to investigate conditions among sharecropping communities in the American South by reporting on the life of one family. The project (famously rejected by Fortune but published in book form five years later as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Three Tenant Families) led Agee to question his own role as a journalist as well as the honesty of journalism altogether, castigating its false neutrality and its underlying brutality as a context. “It seems to me curious, not to say obscene and thoroughly terrifying,” he wrote in the book’s Preamble, “that it could occur to an association of human beings…to pry intimately into the lives of an undefended…ignorant and helpless rural family, for the purpose of parading [their] nakedness, disadvantage and humiliation…in the name of science, of ‘honest journalism’ (whatever that paradox may mean).”

In the foreword to her 2003 project The Innocents, Taryn Simon echoed Agee’s concerns regarding the manipulability of documentation, as well his fear of the imposing nature of context. “Evidence does not exist in a closed system,” she wrote; “. . . Photography’s ability to blur truth and fiction is one of its most compelling qualities. But when misused . . . this ambiguity can have severe, even lethal consequences…[P]hotography’s ambiguity, beautiful in one context, can be devastating in another.” In her most recent body of work, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters: I–XVIII—on show at London’s Tate Modern and accompanied by an 864-page monograph published by MACK—Simon adopts a heightened, evidentiary version of Evans’s “straight” documentary-style, and at the same time entirely undermines it (in the manner of Agee) by blatantly overemphasizing the strictures, structures, and open-endedness of the systems within which such “evidence,” in the form of both text and image, operates.

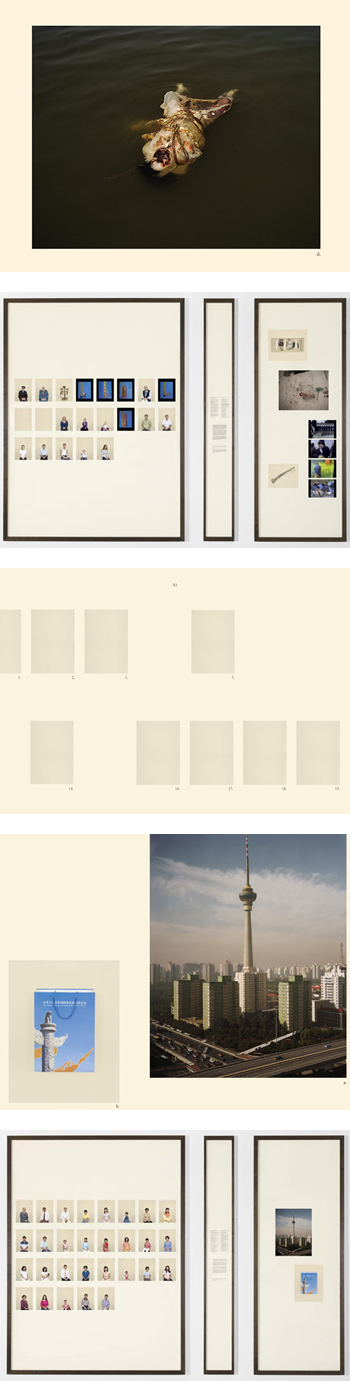

The project delves into eighteen bloodlines around the world and their related stories—albinos in Tanzania; victims of genocide in Bosnia; descendents of Igorot tribesman exhibited at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair (to showcase America’s acquisition of the Philippines); members of a community of Lebanese Druze; a family selected by China’s State Council Information Office to “represent China”; a family in India, alive but officially declared dead as part of a land-grab by distant relatives; and so on. Each bloodline is presented as a chapter in the form of a triptych: a grid of portraits on the left, a series of captions and texts in the middle, and on the right a collection of what Geoffrey Batchen refers to in his accompanying essay as “supplementary images.”

The portraits follow a precise order delineated by ascendency and descendency within the given bloodlines. They are shot in the manner of conventional identity photographs—bare backgrounds, expressionless, straight-on—the images’ “objectivity” so weighted that apart from the basic physical features and fashions of each subject, individual identity is practically erased; more still lifes than portraits. In fact, the most striking images in each grid are those that are empty, the blank wall testifying to the absence of members of each bloodline due to disappearance, imprisonment, disease, fear of kidnapping, lack of visa, refusal to participate, or in the case of many women, the lack of their family’s permission to be photographed due to “social and religious reasons.”

Of course, none of this information is proffered by the photographic grids alone. The texts, presented in the central panels of Simon’s triptychs, identify each subject by name, age, location, and so on, and tell the stories of each bloodline. These are presented in an authoritative and seemingly neutral tone—that of “non-fiction”, of “respectable journalism”—a familiar voice that we have been conditioned to trust but that nevertheless, as Agee pointed out long ago, is by no means unbiased, impartial, or entirely trustworthy.

It is in the third panels, the so-called “supplementary images,” where the bloodlines’ stories take full form. In Chapter I this consists of a location-portrait of one of the living men declared dead; two legal documents – one officially certifying life (through photographs and fingerprints), the other, death (through government letterhead); and an image of an anonymous corpse floating in the Ganges. In Chapter XV (the Chinese state’s “ideal” family) it contains a cityscape with the China Central Television Tower looming over the Beijing skyline, and a photograph of a gift bag given to Simon by the Chinese government. Such images, ephemera collected while investigating these various stories, are coolly photographed but borrow more from Evans’s “documentary-style” than the document. Hinting at both ambiguity and ephermerality – of lineage, identity, truth, fact, and evidence—these endnotes imbue the work with lyricism, visual accessibility and narrative, and at the same time subtly reveal the quiet yet commanding role that authorship plays throughout.

In a 1997 interview, the writer David Foster Wallace—famed for his use of endnotes that practically overrun his primary texts—stated: “It seems to me that reality is fractured right now. . . . The difficulty in writing about that reality is that text is very linear and very unified, and I am constantly on the lookout for ways to fracture the text that aren't totally disorienting….There's got to be some interplay between how difficult you make it for the reader, and how seductive it is for the reader if they are willing to do it. The endnotes [ . . . are] a useful compromise.” Simon’s A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters engages with similarly fractured realities, and explores how notions of history, truth, and identity are (mis)represented and (mis)understood within such realities. By contrasting her wholly “evidentiary” images and texts with surreptitiously powerful photographic endnotes, she undermines the ambiguity of the photographic medium and at the same time harnesses it to convey meaning, narrative, and purpose from the edges of the subject at hand.

Taryn Simon’s A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters: I–XVIII was presented at Tate Modern, London, May 25–November 6, 2011. The series is also on view at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie, September 21, 2011–January 1, 2012; it will have its American premiere at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (exhibition curated by Roxana Marcoci), opening May 22, 2012.

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2012. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.