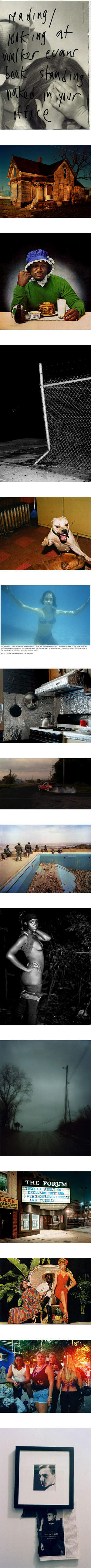

Whatever Was Splendid: New American Photographs

@ 2010 FotoFest Biennial, Houston

March-April 2010

Curated by Aaron Schuman

This essay was first published in Contemporary U.S. Photography (Amsterdam: Schilt, 2010).

Seeking support for what eventually became The Americans (1958), Robert Frank conceded in his 1954 Guggenheim Fellowship application that “‘The photographing of America’ is a large order—read at all literally, the phrase would be an absurdity.” Similarly, to curate an exhibition that represents and succinctly defines the whole of contemporary photography within the United States more fifty years on, read at all literally, seems equally absurd. In practical terms, the country’s current photographic landscape, with its sheer volume and vast variety, offers any aspiring surveyor an expansive visual territory that would be impossible to chart fully or accurately. As Frank also noted, photographs of America are “anywhere and everywhere—easily found, not easily selected and interpreted.”

The same holds true today, if not more so—pictures are anywhere and everywhere, and therefore the task of meticulously sifting through them for potential treasure is a formidable one, which relies not only on an intricate knowledge of the terrain, but also on the occasional shimmer of good fortune. Such an endeavor, at times seemingly futile and ill-fated, is nevertheless incredibly tempting. Despite its limitations, omissions, contradictions, and inevitable imperfections, this venture has within it the potential to instigate some fascinating journeys and to produce a number of valuable insights, into both the country and the photographic medium at large. With that in mind, the challenge becomes twofold. First, and most obviously, it is necessary to examine what photography says about the United States: what is the U.S. today—as a place, a culture, a concept, and so on—and how is it seen, explored, expressed, experienced, and understood through photographs? Second, one is compelled to discern what the United States specifically says about photography: how is photography today—as a medium, apparatus and tool—utilized, shaped, transformed, and defined by those who practice it in, and apply it to, the U.S.? And inevitably, faced with such sweeping motifs and grand concerns, one is led toward the central and perhaps most difficult question of all—where does one begin?

In “Walker Evans and Robert Frank: An Essay on Influence”, Tod Papageorge notes that Evans’s seminal 1938 monograph, American Photographs, was “bound in black…bible cloth, the cover of hymnals.” The book has certainly lived up to its binding in recent decades, having gained a reputation and importance of nearly biblical proportions, particularly within American photographic circles, where its influence can be perceived far beyond Evans’s most literal, obvious, and immediate disciples. And as its title suggests, Evans’s tome might serve as an ideal starting point for an exploration of how the United States is both seen in, and related to, photography. John Szarkowski once wrote, “It is difficult to know now with certainty whether Evans recorded the America of his youth, or invented it. Beyond doubt, the accepted myth of our recent past is in some measure the creation of this photographer, whose work has persuaded us of the validity of a new set of clues and symbols bearing on the question of who we are. …[I]t is now part of our history.”

American Photographs is divided into two chapters—the first very generally exploring people and places, the second reflecting more specifically on the country’s traditional and vernacular architecture. Many have cited how the second set of images in particular, with their formality and directness—their “straight-ness” as it has been coined—has played a significant role in various photographic approaches and concerns of the twentieth century, such as those employed by the New Topographics and the Dusseldorf School, along with their numerous descendants, followers, imitators, and admirers. But if this second chapter demonstrates Evans’s consistency, stoicism, and discipline, the first chapter celebrates the diversity and range of his photographic vision, embracing a plethora of photographic possibilities and expanding the medium’s potential far beyond the strictures of the formally, thematically, or aesthetically delineated series. It is within this chapter where most of the new “American” myths, clues, symbols, and histories that Szarkowski recognized in Evans’s work reside—the laborers, soldiers, and citizens of the city streets; the barbershops, farm stands and shotgun shacks; the main streets, civic statues, and grandiose boardinghouse facades; the cars, cars, and more cars, roaming freely, sitting in neat rows, or lying abandoned by the side of the road; the ubiquitous advertisements, torn billboards, political placards, movie posters, playbills, cryptic graffiti, and meticulously hand-painted storefront signs; the ghettoes, the poor, the homeless, and the flood refugees; the god-fearing family, the loving couple, the man in the crowd, and the lonely, dolled-up girl looking out to sea. This profoundly ambitious and extensive visual collection—found within just the first fifty pages of Evans’s book—not only serves as a document of America in Evans’s time, but also prophetically catalogues a landscape, character, cultural experience, and set of symbols that remain both poignant and familiar within the country to this day. And in particular, this index bears an uncanny resemblance to the America described and preserved within photography since Evans, including that of today’s most exciting, perceptive, intelligent, and original practitioners.

“The tracing of influences in photography is at best a perilous business,” Szarkowski reminds us, and there would be little sense in trying to determine the precise effect of Evans’s work on contemporary photographers seventy years later, as it has inevitably been filtered through many generations of creative experimentation, technological advancement, cultural change, and critical evolution. But looking at American Photographs today, it is difficult to deny its lasting impression, and it is hard not to postulate that—even in cases where its influence is not direct—Evans’s eye certainly resides in the medium’s collective unconscious, particularly in respect to the photographing of America. “The modern photographer, like everyone else, is bombarded by a continuous flood of camera images,” Szarkowski continues, “an assault on his eyes so massive and chaotic that he often does not himself know which pictures have left a residue of challenge in his mind. The influence of an exceptional photographer works less through his pictures’ first impact than through their staying power: their ability to implant themselves like seeds in a crevice of the mind, where the slow clockwork of germination begins.”

In the introductory essay written for American Photographs in 1938, Lincoln Kirstein stated:

“[Evans] can be considered a kind of disembodied burrowing eye, a conspirator against time and its hammers. … Here are the records of the age before imminent collapse. His pictures exist to testify to the symptoms of waste and selfishness that caused the ruin and to salvage whatever was splendid for the future reference of the survivors.”

Over the course of the last eighteen months, the economic, social, cultural, and political climates of both the United States and the world at large have frequently been likened to those of Evans’s time. Despite our survival of the Great Depression, as well as the rest of the twentieth century, similar symptoms of waste and selfishness have recurred, and once again we find ourselves in an age that is seemingly threatened with, if not in the midst of, imminent collapse. The exhibition "Whatever Was Splendid" represents an attempt to explore the parallels that exist—in America and in photography—between our own time and that of Evans, as well as the enduring power of American Photographs as discerned through contemporary photographic practice within the United States. The artists who are included in this exhibition undoubtedly reflect the originality, ingenuity, and multiplicity of voices and visions that can be found within current U.S. photography, but they all inherently possess a familiar “burrowing eye” as well, and share Evans’s determination to record, testify, and salvage what they can of their own precarious age for potential future survivors.

In Down These Mean Streets (2008-2009), Will Steacy boldly investigates America’s inner cities—“the neighborhoods you wouldn’t want to be in at night; the parts of towns you drive through, not to,” as he describes them himself—places where collapse has already occurred and where any sense of hope or salvation has seemingly been abandoned long ago. Like those of Evans, Steacy’s images act as “lyric documents” (Evans’s phrase, as noted by Papageorge), recording frankly and with striking clarity the decay, dilapidation, and desolation that confront him on his nocturnal urban expeditions, whilst at the same time evoking a subtle yet physically palpable atmosphere that lies just beneath the visible surface, in this case one of fear, danger, and desperation. Within this series, a surprising number of Evans’s own “clues and symbols” crop up in the details—an abandoned car, a handsomely built Victorian house, a barbershop sign, and so on. Yet such clues have been further exposed and speak distinctively to our own time: the car has not only been scrapped, but torched as well; the house is boarded up and falling apart; and the barber’s sign is all but entirely obscured by gangland tags and graffiti. Furthermore, Steacy adds many of his own, more contemporary, symbols to the mix, including the deserted towers of a half-built housing project, a sidewalk stained with blood, a window shattered by the impact of a bullet, and a roadside memorial to a murdered brother. As much as his approach, attitude, and visual vocabulary might echo those of Evans, these are records that surely testify to an urban experience of the twenty-first century.

With Your Golden Opportunity is Comeing Very Soon (2008-2009), RJ Shaughnessy also hits the streets with his camera, or rather, he photographs where the streets themselves have been hit. Trawling through the parking lots, the avenues, and the long boulevards of Los Angeles at night, Shaughnessy has found and cleverly brought together a collection of easily overlooked sites where the street and its furniture have literally been scarred by the physical impact of automobiles. Signposts have been kinked and crooked, and now point in the wrong directions; plaster walls and cement pillars have had their smooth surfaces violently scraped off; once neat fences have been twisted, disfigured, and distorted; thick steel bollards have been bashed and bent, and now look impotent and forlorn. Captured straight on, in black-and-white, with a powerfully harsh flash, the images take on an air of vintage evidence, like crime scenes captured under the blinding light of intense scrutiny. And what at first seem to be the insignificant remnants of forgotten minor accidents become suggestive traces, which bear within them much wider implications. At the same time, Shaughnessy’s photographs possess a certain graphic if not abstract sensibility—rather than signaling accidents, the pictures suggest that his subjects could be the oeuvre of a deconstructivist sculptor, catalogued by a photographer possessing strong formalist inclinations. Although the legacy of American Photographs may not be as discretely obvious in Shaughnessy’s series as it is within Steacy’s, the spirit of Evans is certainly embedded within it in that Shaughnessy has similarly, in the words of Kirstein, “elevat[ed] the casual, the every-day and the literal into specific, permanent symbols.” “A garbage can, occasionally, to me at least, can be beautiful,” Evans once wrote. “Some people are able to see that—see and feel it. I lean toward the enchantment, the visual power, of the aesthetically rejected object.”

Todd Hido’s work possesses a similar sense of enchantment with the rejected, but it leaves the city behind, first turning to suburbia in Foreclosed Homes (1996-1997) and then retreating to rural byways in A Road Divided (2008-2009). Yet Hido’s imagery suggests that he is less interested in the spurned objects that he photographs than in the light, the space, and the atmosphere that inhabit them, leaning more toward the lyrical rather than the documentary side of the photographic spectrum as delineated by Evans. In both series, Hido certainly elevates the everyday, yet does so not through the presence of things, but rather through their absence, and the subtle aura that is left behind. The interiors presented in Foreclosed Homes—rooms almost entirely stripped bare, with only the soft light left seeping in through their windows—certainly testify to both specific events and a wider state of affairs within America today, but they do so in a hushed whisper. Similarly, the bleak and bleary byways of A Road Divided seem to hum quietly in a minor key, reflecting a long and troublesome journey ahead while also hinting at the possibility of change just over the horizon.

Greg Stimac’s video Peeling Out (2007) presents a sequence of country roads quite similar to those found in Hido’s body of work, but rather than humming, it screeches and roars as a series of pickup trucks, muscle cars, classic roadsters, and Trans Ams race with unjustified urgency into the distance. With each cut to a new road and a new vehicle, a distinct sense of frustration, anger, and aggression grows as tires spin and smoke rises, which then gradually dissipates as the cars ease out of view. Despite the fact that this work consists of moving images, there is a straightness and determined stillness to Stimac’s camerawork—a matter-of-factness—that recalls that of Evans and lends a familiar “visual power” to both the subject before the camera and the artist behind it. Again, as Evans himself stated, “There is a deep beauty in things as they are.”

Stimac employs a similar visual approach in Car Wash (2006), another video work in which the camera stands stoically and straight-faced on the side of the road as its subject intermittently screeches—in this case, a high school girl posing for passing cars with a handmade sign while screaming, “Car wash! Getch your car washed! Over there! Woo-hoo!” repeatedly over the rush of traffic. In one sense, the piece records the same naïve entrepreneurial spirit so often celebrated by Evans: one is reminded of the iconic image of two young boys holding up watermelons by a roadside fish market and fruit stand—its signage having been painstakingly hand-painted as well—which resonates strongly within the first chapter of American Photographs. Yet as the video progresses, the girl’s incessant fake smile, skimpy neon-pink dress, and perky cheerleader moves seem to contaminate the innocence of the scene with a somewhat exploitative and overtly sexualized tone, more typical of American commercialism today. Metaphorically at least, it could easily be surmised that a girl standing on a street corner, dancing and waving in a skin-tight outfit as passing drivers honk and shout, is selling more than a car wash, no matter what her sign might say.

Craig Mammano’s A Few Square Blocks (2006-2009), a collection of remarkably intimate portraits made in New Orleans, employs an unapologetic rawness in style and approach that shifts notions of sexualization and exploitation from the implicit to the explicit. His subjects, women who pose both clothed and unclothed, oscillate between elegance and desperation, confronting the viewer with a brazen openness that is equally refreshing and disconcerting. Both literally and figuratively, these women bare themselves to the camera, and assume a nakedness of spirit as well as of body that is rarely achieved within the contemporary photographic portrait. Instead of cloaking the female—and in particular the female nude—in sexual performance, fantasy, lust, and desire, as so much of American media does today, Mammano’s roughly hewn pictures genuinely uncover his subjects’ individuality, presenting them as candidly as possible. Both the photographs and the women possess, in Evans’s words, a “purity and a certain severity, rigor, simplicity, directness, clarity…without artistic pretension in a self-conscious sense of the word.”

With a similar sense of rigor, simplicity, directness, and clarity, Jane Tam’s Foreigners in Paradise (2006-2008) examines the hybridization of culture and national identity that she herself has experienced within her own Chinese-American home. Having adopted an Evans-like “straight” strategy, Tam sets out not to explore and define symbols representative of the United States at large, but rather to discern what clues of her grandparents’ Chinese heritage remain as the family becomes more and more Americanized with each successive generation. Within a conventional American setting, small details—such as red flip-flops left by a door, the walls of a kitchen protected with tinfoil, and her grandparents scouring the local park for ginkgo nuts brought down by heavy rains—all point to remnants of traditional Chinese life. And yet the photographic approach and surrounding mise-en-scène suggest that, for Tam and the other relatives of her generation portrayed in the photographs, such sights are as American as any other.

Alternatively, Richard Mosse follows the United States, its military might, and its frontline soldiers into foreign lands—the deserts of Iraq—where he cunningly extracts some of the American sights and symbols that they have transported with them from home. In The Fall (2009), the prevalent theme of the derelict automobile returns yet again, although in these instances the vehicles have not only been abandoned and torched, but riddled with bullets and blown to pieces by bombs as well. The metal corpses lie destroyed and disgraced in a vast no-man’s-land, at once terrifying testaments to war and eerily beautiful memento mori, soon to be subsumed by the approaching sand storm.

In his photographic series Breach (2009) and its video counterpart, Theatre of War (2009), Mosse shifts his tone from the sublime to the ridiculous, documenting soldiers as they leisurely occupy and inhabit the lavish ruins of one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces. They lounge by a giant turquoise swimming pool, casually lift weights in sun-drenched courtyards, and calmly smoke cigarettes whilst taking in the view. Such scenes would not seem out of place in the mansions of Malibu or on the boardwalks of Venice Beach if it weren’t for the surrounding rubble, the combat fatigues, the inconspicuous heavy weaponry, and the scorched Arabian desert stretching off into infinity.

And finally, in his video piece Killcam (2008), Mosse returns home to a veteran hospital with some of the wounded, interspersing various sequences of recovering amputees playing Iraqi-themed combat video games with digital battle footage—found leaked online—of real American missile strikes and assassinations from the ongoing war. In fact, Killcam cleverly confuses the line between image and reality, and ultimately calls into question the premise of the ‘real’ United States altogether when one of the repatriated soldiers explains over Killcam’s closing credits, “Actually, coming back here is stepping back into a computer game. Over there is real life. …[T]here’s less reality over here. People only see and hear what they want to.”

It is important to note that Evans was perfectly conscious of, and fascinated by, the inherent relativity, imperfect subjectivity, and deceptive clarity of the photographic image, both in terms of others’ images and his own. Szarkowski once wrote that “a beginning photographer hopes to learn to use the medium to describe the truth; the intelligent journeyman has learned that there is not enough film to do that,” and Evans was certainly one such journeyman. As his title affirms, American Photographs is about both a country and a medium in equal measure; its opening sequence of images—License Photo Studio, Penny Picture Display, Faces, Political Poster—more than hints at the fact that the book is as much an interrogation of photography as it is of America, if not more so.

Similarly, in The Week Of No Computer (2007-2009), Michael Schmelling focuses not so much on any particular subject matter in the obvious sense, but rather on the process of looking for, looking at, making, and manipulating photographic images from the perspective of one who is obsessed with, and heavily involved in, the medium in its many contemporary forms. Like Evans, Schmelling embraces the act of openly referencing photography , even making pictures of pictures: one photograph captures a William Eggleston print casually hanging on the wall of a corporate-looking corridor, and another shows a framed portrait of a young Evans himself with a spookily similar picture of Hedi Slimane, torn from The New Yorker, pinned beneath it. Furthermore, amongst his traditionally “straight” photographs, Schmelling incorporates a number of experiments, including double exposures, photocopies, creased posters, flatbed scans, and pictures laid on top of other pictures, as well as self-referential snapshots that curiously explore his own surroundings as a photographer: stacks of Kodak print boxes, a Polaroid image of his own camera, a darkroom enlarger, exposure notes, outtakes, tearsheets, contact sheets, and so on. Again, there is certainly a “rigor, simplicity, directness, and clarity” at work here, but there is also a fascinating self-consciousness that, through its sincerity, manages to escape the dreaded realms of “artistic pretension.” Perhaps the project is cryptically summed up best by the note Schmelling scrawled to himself on a picture he pulled from a book and then scanned into a diaristic image of his own: “reading/looking at walker evans book standing naked in your office.”

Hank Willis Thomas’s Unbranded (2006-2008) is likewise interested in interrogating the photographic medium itself and, more specifically, what he calls the “empire of signs”—or what Roland Barthes called the “what-goes-without-saying”—in advertising photography. Thomas also makes pictures out of pictures, in this case appropriating and manipulating magazine advertisements from the last forty years that have targeted African American consumers or featured African American subjects. The resulting images—stripped of their branding and context—poignantly reveal a number of disturbing stereotypes, generalizations, and aspirational assumptions that reside deep within contemporary American culture, and uncover a number of painful truths about the country’s attitudes regarding race, gender, class, and ethnicity. Perhaps even more curious is the fact that Evans’s first chapter contains a similar experiment: two cropped details of advertising posters featuring African Americans, both entitled Minstrel Showbill, from 1936. And for all intents and purposes, not much seems to have dramatically changed in terms of the visual language surrounding race in America, despite the passing of more than seventy years.

In some ways, Nirvana (2007-2009), a series of photographs collected and then re-presented by Jason Lazarus, reverses Thomas’s approach in that it takes amateur snapshots (never originally intended for general consumption) and provides them with a purely public platform and context, enabling the photographs to both individually and collectively reflect much broader cultural issues. To make this work, Lazarus posed a question: “Do you remember who introduced you to the band Nirvana?” He asked other people to send him an answer written on the back of a photograph, and then scanned, enlarged, and framed a selection of the submitted images, with their corresponding texts handwritten onto the prints themselves. Remarkably, this simple question provoked a number of astonishingly tender and painful responses, which together, amongst other things, paint a subtly moving portrait of male roles, relationships, identities, and masculinity within the United States today: “Dave…introduced me to Nirvana…he carved my name into his arm”; “Mikey, my mom’s second husband…he was around until I was 13”; “My father introduced me to all grunge music”; “I listened to Nevermind for the first time with [my uncle]…I lost him to AIDS in 1994.” In addition, these photographs and their accompanying texts convey a sincerity, an authenticity, even a sense of truthfulness that most of today’s publicly exhibited photographs lack, specifically because Nirvana’s imagery is not the considered creation of a single, purposeful, “professional” photographer, but is instead the result of a large, collective effort evidencing very private, personal memories.

Finally, Tema Stauffer, who focused American masculinity and male adolescence in her portraiture series The Ballad of Sad Young Men (2008), includes several such portraits within her broader and more extensive body of work: American Stills (1997-2009). Returning to the eclecticism of the first chapter of American Photographs, and under a similarly sweeping heading, Stauffer presents an assortment of sharply poetic observations of a country that at times can be angry, melancholy, brutal, and cold, but can also be enchantingly majestic and profoundly moving. Throughout the series there is a critical yet immensely forgiving sense of real compassion at work—a profound love for the subject, with all of its flaws—which strikes straight at the soul of the matter, in the most ordinary places and everyday moments. Rather than simply testifying to waste, selfishness, imminent collapse, and so on, Stauffer’s Stills represent a truly committed and heartfelt attempt at unearthing the “splendid” from the “whatever” of contemporary America.

At its heart, "Whatever Was Splendid" is centrally informed by the legacy of American Photographs, and by Evans’s vital contributions to the nation’s photographic traditions, as well as the practice of photographing of the United States in general. But it is by no means intended as a nostalgic update or sentimental plea for photography (or, for that matter, America) to return to its past. As much as Evans’s legacy has provided both the inspiration and a reinforcing framework for the exhibition (and, in many cases, for the work of the participating photographers), "Whatever Was Splendid" is first and foremost the manifestation of a fertile terrain—that of contemporary photographic practice within the United States—where Szarkowski’s “slow clockwork of germination” continues to develop, adapt, propagate, and flourish in a variety of fresh and fascinating ways. Consciously or not, all the photographers represented here have, in their own distinct ways, expanded upon many of the themes, strategies, clues, symbols, “certain sights, [and] certain relics of American civilization past or present” first glimpsed in American Photographs. And like Evans, they have both reinvigorated American photography and redefined their country—conceptually, aesthetically, culturally, politically, historically, photographically, and so on—within very contemporary terms, celebrating both the United States and its photography, as Kirstein put it, “with all [its] clear, hideous and beautiful detail, [its] open insanity and pitiful grandeur."

Essay by Aaron Schuman

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2010. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.